AFR MAGAZINE DECEMBER 2022

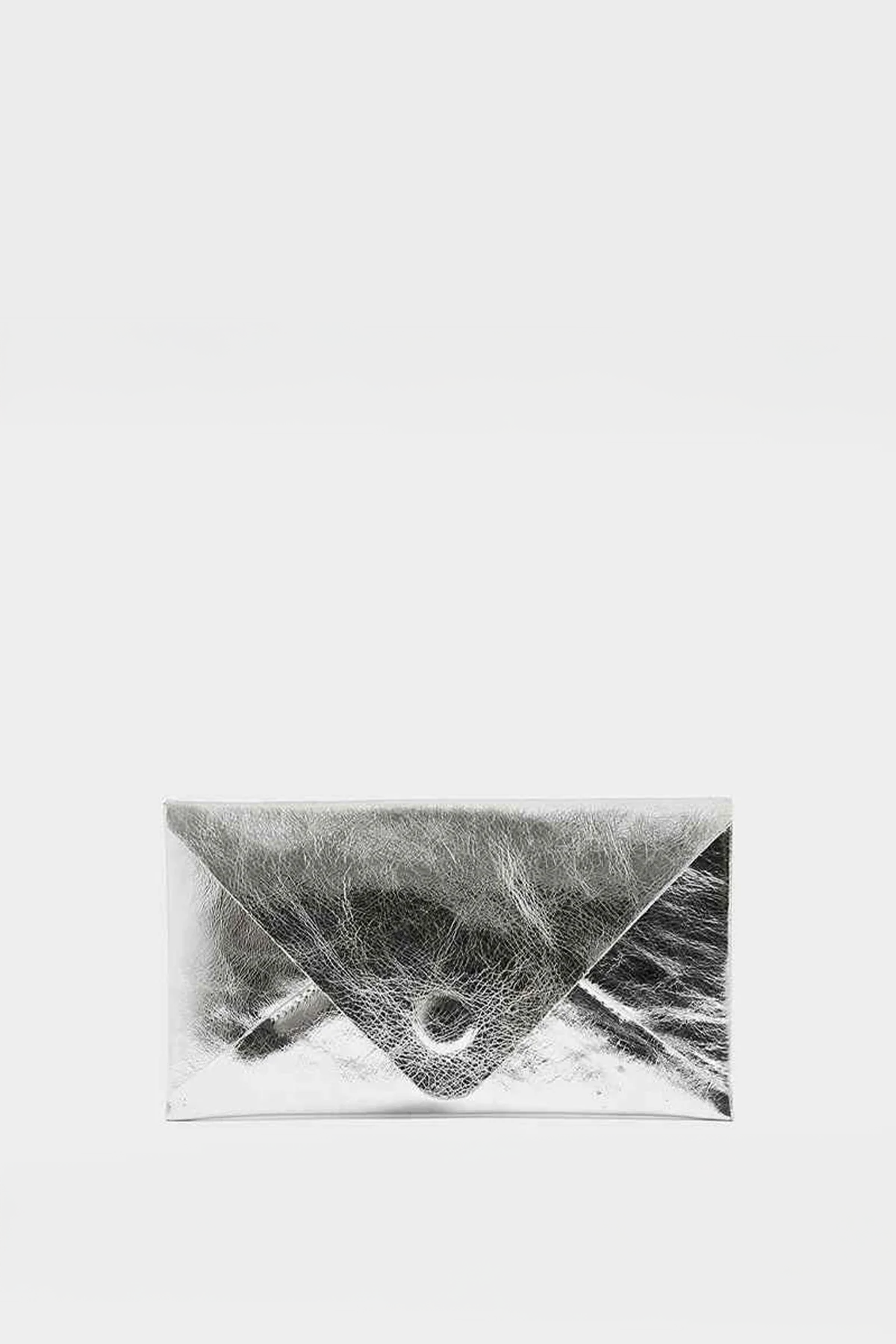

HOW DO YOU GET SOMEONE TO SPEND $900 ON A BAG? If you're Amanda Briskin-Rettig, you show them how it's made. Most companies like to keep the prying eyes of their customers away from their manufacturing. Briskin-Rettig, who owns luxury accessories brand A-Esque, thinks this is rubbish. Her flagship store on Swan Street in Richmond is also her atelier. Come in. Take a look around. And if you like what you see, take a bag home with you.

Amanda Briskin-Rettig

"People often ask me, 'Why would someone spend $900 on a bag? she says. "And it's something intangible. Yes, we are selling quality and longevity. But there is also something special about them that is more than the sum of their parts. You can get a salad at the airport and it has the same ingredients as one you buy at a cafe, but it's shit. It's the same with fashion - it's the way it is made, the people making it. And sometimes, you just really need to see it.

"A-Esque is "deliberately small and slow", particularly when compared with Briskin-Rettig's former business, accessories behemoth Mimco, which she sold to private equity for more than $40 million in 2007. Mimco was focused on helping women find their style and experiment with it. For A-Esque, founded in 2012, Briskin-Rettig's focus is on the making and provenance of products. "My customer knows her personal style. She's not coming to me to discover that. She knows what she likes, she wants the best version."

Briskin-Rettig has also revised how she finds those customers. In the pandemic she shut down A-Esque's Collins Street store, having already shut down her stores on Chapel Street in South Yarra and the Strand Arcade in Sydney. She also ditched her concessions in David Jones and ended wholesaling to Lane Crawford in Hong Kong. It's all in service of doubling down on her Melbourne flagship, which is also the workshop. Customers can see their bags made in real time. Hang around long enough - about an hour - and you can see pieces of leather and metal hardware come together to become a fully formed bag right in front of you by A-Esque's team of 10 artisans. And then, you can take it home.

"I like the challenge of desire," Briskin-Rettig says. "I like making things that, sure, people don't need. It's not water or food. But how can I make something so beautiful that it inspires someone to want it? To me, that's exciting."

The point, she says, is beauty. And part of the beauty, she says, is showing how things come together. Needless to say that you can't achieve the same effect online. For Briskin-Rettig, physical retail is non-negotiable, even - or perhaps especially - in a digital world. "But it's got to be more than stuff in a shop. It's services, it's curation, it's experiential. Because retail has a real amplification factor. It literally brings people in. And people are everything."

Last year, as much of the country emerged from a second year of COVID-19 lockdowns, the CEO of a leading online retailer told me she could not imagine shopping in a physical store ever again. The parking.

The queues. The lack of inventory. The middling staff. It was a hassle, she said, and so far from what bricks-and-mortar once was. She recalled working at a department store in her early 20s and being told that if a customer requested a dress that was not sold at the store, it was her job to go out and find it, buy it, and sell it to the customer. Nothing was too much trouble; retail existed to solve problems for the client. Those days were over, she said, and shopping had become so transactional that she couldn't foresee a time when she would be drawn into a boutique, let alone a shopping mall, again.

Her thinking was in line with much of consumer sentiment and retail forecasting during the pandemic. Foot traffic plunged as we worked from home, and online spending grew by 57 per cent in 2020, according to Australia Post data. It replaced physical stores as the main retail channel for everything except groceries, accelerating a trend that had seen clicks chip away at bricks. Well before the pandemic, David Jones and Myer were looking to reduce their rent by closing stores. Indeed, across the world, giants such as Gap and Zara are shutting stores to focus on CBD flagships. Amazon Prime, launched in Australia in 2018, now has 2 million members here who can access next-day delivery on many items, including fashion and accessories.

And yet, according to Monash University's annual Retail Monitor, shoppers are once again making most of their purchases in-store rather than online for all categories of non-grocery products (except for media and travel). Given the choice between physical and online stores, most shoppers say they would rather shop in-store. Flagships are rolling out apace; in Sydney, Cartier is about to open a 783-square-metre flagship on the corner of George and King streets. In Melbourne, David Jones, so eager to lose that pandemic weight in the form of rental overheads, bulked up with a renovated Bourke Street store, at a reported cost of $50 million. Brands such as July, Stax and Henne that began as direct-to-consumer online stores have opened retail spaces. And Chadstone in Melbourne is embarking on a $485 million redevelopment.

For all the attention given to online shopping and its threat to physical retail, we still like to go to the shops. And shopkeepers are finding new tricks to keep us coming back for more. Among them is Jason Minty, who's having a homecoming of sorts. The co-owner of Potts Point institution Becker Minty, which celebrated its 15th birthday this year, is about to open his second store - in Hobart. "I always wanted to open there and the time was never right," says Minty, who was born in Tasmania's capital. "But I spent time there last summer and I thought, it's ready. My heart has never left the city." The tourist-led MONA crowd, as well as an influx of new locals post-pandemic, means Minty feels confident that his chi-chi interiors, art and jewellery offering will take off on the Apple Isle.

The new Becker Minty will open in mid-December in a 1960s-era building on Salamanca Place, abutting the famous row of 1830s Georgian warehouses. At 200 square metres, it will be twice the size of Becker Minty's Sydney store, and will have a dining venue featuring Tasmanian produce and wine. But most of it will be retail, a fresh offering in a city where the shopping has stayed static as food and beverage options have leapt ahead.

"Becker Minty has always been about showing our customers the best of everything," he says. "There was never a business plan or a big strategy. We just wanted to bring beautiful things from all over the world into Australia." Minty, who spent most of his pre-retail career in customer service at Qantas, says the key to his success has been showcasing a unique mix of inventory, the kinds of objects you simply can't find anywhere else, beautiful pieces you want to gift or treasure for yourself. For him, online sales are a fraction of the business and act as a stopgap rather than a solution. "Our customers know us," he says. "We do online sales but they're more likely to be through text message or phone call, or even FaceTime, where we take them through the store."

Samantha Ogilvie's eponymous boutique on Brisbane's James Street operates in much the same way. Before COVID-19, she didn't offer e-commerce at all. "We never had the time to do it," says Ogilvie, who opened in 1997. "It was only when the store had to shut that we thought,

'We'd better do this.' But two years later, her clients, mostly well-to-do professional women in their 30s and beyond, prefer to shop in-store. And she gets it. "People like to say that buying online is quicker and easier," she says. "But actually, when our clients come in, they can come to our private showroom, near the main store, and we can choose an entire wardrobe for them if that's what they want. They can try it on quickly, we can suggest things, we all work together and then they're done. They don't have to return anything. They don't have to think, 'Now I need a pair of shoes, where do I get them from?' We do all the hard work for them. And we give them champagne while we're doing it."

It's a sentiment Patrick Johnson has tapped into, too. Johnson, the omnipresent tailor, has just opened a retail space for his Femme spin-off brand in Sydney's Paddington, a few blocks over from his menswear store.

Just don't call it a store. "I wanted it to be like a home. But not, you know, a Paddington terrace," he says. It is a Paddington terrace, but Johnson's brief to his interior designer wife, Tamsin, was "Liberace's powder room without the gold", a directive she has, frankly, nailed. Walls are hand-painted in sage green with a marbled effect, accented by framed Coen Young photographs; fashion magazines are stacked on the mid-century lucite coffee table; upstairs, a set of exceedingly distinct aquamarine frosted-glass cactus sculptures takes up a corner of the room. Oh, and there just happen to be racks of exquisitely tailored vests, shirts, blazers and pants available to you, should you want to try some on.

Johnson's Paddington takeover (he and Tamsin have offices down the road, and their menswear store on nearby William Street) echoes the latest retail trend towards high-street precincts over shopping centres. In Melbourne, vacancy rates on high streets have shrunk - Chapel Street had an empty rate of 18.7 per cent in 2021 that's now down to 10.7 per cent, while the CBD's vacancy rate has risen by 1.7 per cent. In Sydney, landmark buildings along Oxford Street, challenged by the 2014 advent of lockout laws, will undergo a $200 million renovation to be completed by 2024, adding 2300 square metres of retail to the once-thriving strip.

"For us, bricks and mortar is essential," says Johnson, who also has showrooms in the Sydney CBD, Melbourne, New York and London. "It's about experience. Our customers want to come in, get their wardrobe sorted and move on. A lot of our customers won't have ever bought anything online - this is their preference." He says he is a "merchant at heart" and sees online retail as purely transactional. "Online retailers are great, and very efficient, but there's not a lot of connection. Our role is to listen to customers and figure out what they want and need in life. Doing that online is very hard. In fact, I would go so far as to say it is impossible."

Shannon Thomas is busy when I arrive at Deirdre, The Sydney womenswear boutique she opened in 2010. "That looks great on you," she tells a customer. "But if you're not feeling it, I have a few other ideas." The customer has to leave, but it's no problem. "T'll bring them to the Bondi store this afternoon. I know that's closer for you."

Thomas' store is a slim bolthole on South Dowling Street, just off bustling Oxford Street. Here, she stocks party dresses by cult Polish designer Magda Butrym, US label Area, Alex Perry and Christopher Esber, among others.

What it lacks in space it makes up for with big evening-wear energy. If you are in the market for a neon-green minidress or a pair of feather-hemmed pants, you're in the right place. "I loved fashion and I thought nobody had the cool things," says Thomas, who opened the store when she was 23, working nights at Justin Hemmes' Ivy nightclub to make ends meet. "Every store had the same clothes, everyone did the same [inventory] buy." She recalls going to another store at the time and seeing six sales assistants behind the counter, all wearing variations of the same Sass & Bide dress. "I wanted Rodarte. I wanted Kit Willow, but the stuff she wasn't selling at the department stores. I wanted Kym Ellery. I had Aje before they had other stockists."

Thomas, who now has three stores and is about to open a fourth on James Street in Brisbane, is frank about the risks of physical retail. She has no financial backer and buys every piece of inventory up front, reducing the burden on the designer. "Taking on that risk myself is hard," she says, "but I also know that if I believe in a designer, my customers will, too." The store, she says, is "a love project". "I am obsessed with it. It's in my best interests to let other people do the merchandising and talk to customers, and for me to focus on the bigger stuff. But I can't help myself. I love being here. I love dressing people. Sometimes when it's quiet I'll redo the windows two, three times, and nobody has even come in."

Running a physical store, of course, is expensive. Rent, lowered during the COVID-19 lockdowns, is back to pre-pandemic rates. Staffing, like everywhere, is an acute challenge. But there are all sorts of benefits from having a physical space. Briskin-Rettig says A-Esque's atelier doubles as a content studio, bringing the handmade craftsmanship of her bags to its online audience. In New Zealand, independent handbag designer Jessie Wong has established three "lounges" for her brand, Yu Mei, where her audience of young female customers can hang out, have a coffee, and buy a bag if they like. At Sarah and Sebastian, customers can come in to buy jewellery, but for many the pull to store is about services, such as ear piercing or having a bracelet soldered around your wrist. For Shannon Thomas, the store acts as a billboard, offering its own organic publicity. "People see it, they remember you," she says. "I think online is more competitive, because it's a lot harder to stand out. And what online retailers pay in Google Ads is probably more than what we pay in rent."

Minty is similarly evangelical about a place of one's own. "We don't need our customers to come in every week. Physical retail is worth it even if people only return once every six months." And even though Thomas' customers at Desordre are mostly in their 20s and 30s, and therefore primed to shop online, she says they prefer to visit her in store. "Physical retail feels more important to me. This is touch and feel. This is real life." There is an element of discovery, too, she says. "People come in looking for a pair of jeans but they see a pink dress and sparkly sunglasses and that's what they walk out with. It's exciting and fun."

Like Thomas, Ogilvie has an obsession with hard-to-find inventory. She knows her customers do not have time to scour the world looking for their next item of clothing; that is her job. Many of the designers she stocks are exclusive to her in Australia, such as fashion-editor favourite Tibi, La Prestic Ouiston, Veronica Beard and jeweller Yvonne Leon. "There was no great science to it," Ogilvie says. "Every other boutique was focused on Australian clothing but I wanted to do international. Net-A-Porter wasn't around, and I wanted wearable fashion from contemporary labels. I wasn't looking for super high-end luxury pieces, or even the hottest labels at the time. I wanted things I could wear and love; I knew customers would follow."

The store is now 24 years old and Ogilvie - and her clients - have grown with it. "The inventory has changed and evolved," she says. "I don't want the customers to be cookie cutters of each other. It shouldn't be about the Samantha Ogilvie look, it's about coming in and finding your style." With such a large assortment of products, staff training is crucial. "We play dress-ups," she says, "and we style each other, so that when customers come in we know what we're doing." There is a magic to this, she says, that she knows cannot be replicated online. "You can chat to a person online, but there are limits. We know our customers, we have been wardrobing them for a very long time. We never do the hard sell, but the biggest compliment is when someone says to me, 'I never would have picked that out, but I love it."

Coming out of the pandemic, says Briskin-Rettig, customers' expectations are higher than ever, and much of this has to do with the lack of friction in online retail. "You are competing with global conglomerates who have big wallets and big resources," she says. "They can undercut pricing, they can offer delivery in hours sometimes. And for the customer, that becomes the benchmark, even if you are the shop next door with two employees." It's her desire to minimise this that has led to the reshaping of her retail strategy. The more control she has, the better she can ensure customers have the experience they now demand. She does not discount, there are no sales. VIPs are "treated well", but that's all she will say. There is also, naturally, an online store, which now sells more than her previous retail stores once did, combined. Briskin-Rettig says she thinks this is because she has built trust and authority in store, which has led to an uptick in online spend.

Shopping centre operators know about building trust, and eliminating friction, better than most. At Chadstone, in Melbourne, virtually every barrier to entry has been destroyed. Its car park, the third

biggest in Australia (behind Sydney and Melbourne airports) boasts 10,000 spaces (all free) with a further 11,000 coming (there's valet parking, too, of course). You can shop each store via an app and have the products delivered to your car, so you don't even have to set foot inside the centre. And if you are shopping in-store, and your arms are feeling a little fatigued, why not hire a personal butler to carry your bags for you?

"It's about making it special," says Amy Wootton, Chadstone's head of marketing. "Even in a big centre like Chadstone, we are always asking ourselves, 'What can we give customers here that they can't get anywhere else?' We are quite single-minded about that."

In many ways, says Patrick Johnson, new retail is not retail at all. It is service. "On a Saturday afternoon, if you come to the Paddington store, it's packed," he says. "There'll be guys in there hanging out in between their kids' soccer games, or coming in for a coffee, or just saying hello. We love it. I always tell my staff, we are in hospitality and we happen to make clothing." He pauses to laugh gently. "You should see how many restaurant bookings I make for clients. People are always asking, 'What's the best Italian in Sydney? Where should I go for breakfast?' Your clients are everything, you want to help them, because without them, nothing exists."

Shannon Thomas agrees. "I have all these spreadsheets for different events - school formals, the races, even big weddings. And I'll make sure that I don't sell the same dress for the same event." That, I say, sounds like a huge investment of her time. "Yes, absolutely," she says. "But I would much rather sell one dress to one person, and know that she will come back to me for years, because she trusts me, than sell the same dress to 10 girls and have egg on my face. Because ultimately, it's not really about the dress at all."

Written by Lauren Sams