Vogue Living Magazine May 2023

What’s in your bag? It’s the question behind Vogue’s serial interrogation of identity and celebrity through the everyday stuff it totes around. Today, it targets Melbourne’s Amanda Briskin-Rettig, design-founder of stealth accessories label A-esque, who blind stitches life’s learnings and loves into handcrafted carryalls with a cryptic name.

“It means in the manner of ‘A’ — the letter attaching to the most memorable experiences and moments in life; the things that last,” elucidates Briskin-Rettig of her brand’s best-in-class inference as she drops a deep pillowy leather pouch coloured “elephant” on a marble-topped Knoll table in her kitchen. The space is a dazzling contra-post of contemporary art, commercial-grade cooking equipment and large-format florid Italian tiles. There are views to graphically bold garden and white Finnish Vitsoe shelving, displaying objects “merchandised” by Briskin-Rettig with a near-Darwinian consideration for their species classification by period, posture, material and culinary use. Clearly, one can never have too many candelabras. “I’ll tell you what’s in my bag,” continues the high-energy entrepreneur famed for building Mimco from early marketing experience and the want for a bag that didn’t exist into a fashion phenomenon that clinched a private equity bid and buy-out in 2007. “There’s a lot of observation, a love of life and colour, deep connections with friends and family [including three sons] and endless curiosity. I’m always looking around and inquiring.”

It’s not the usual grab bag of object should-haves suggesting a woman of artfully contrived self-effacement, but rather emotive, intelligent abstracts that communicate A-esque bags are declarations of intent rather than shouty manifestations of trend.

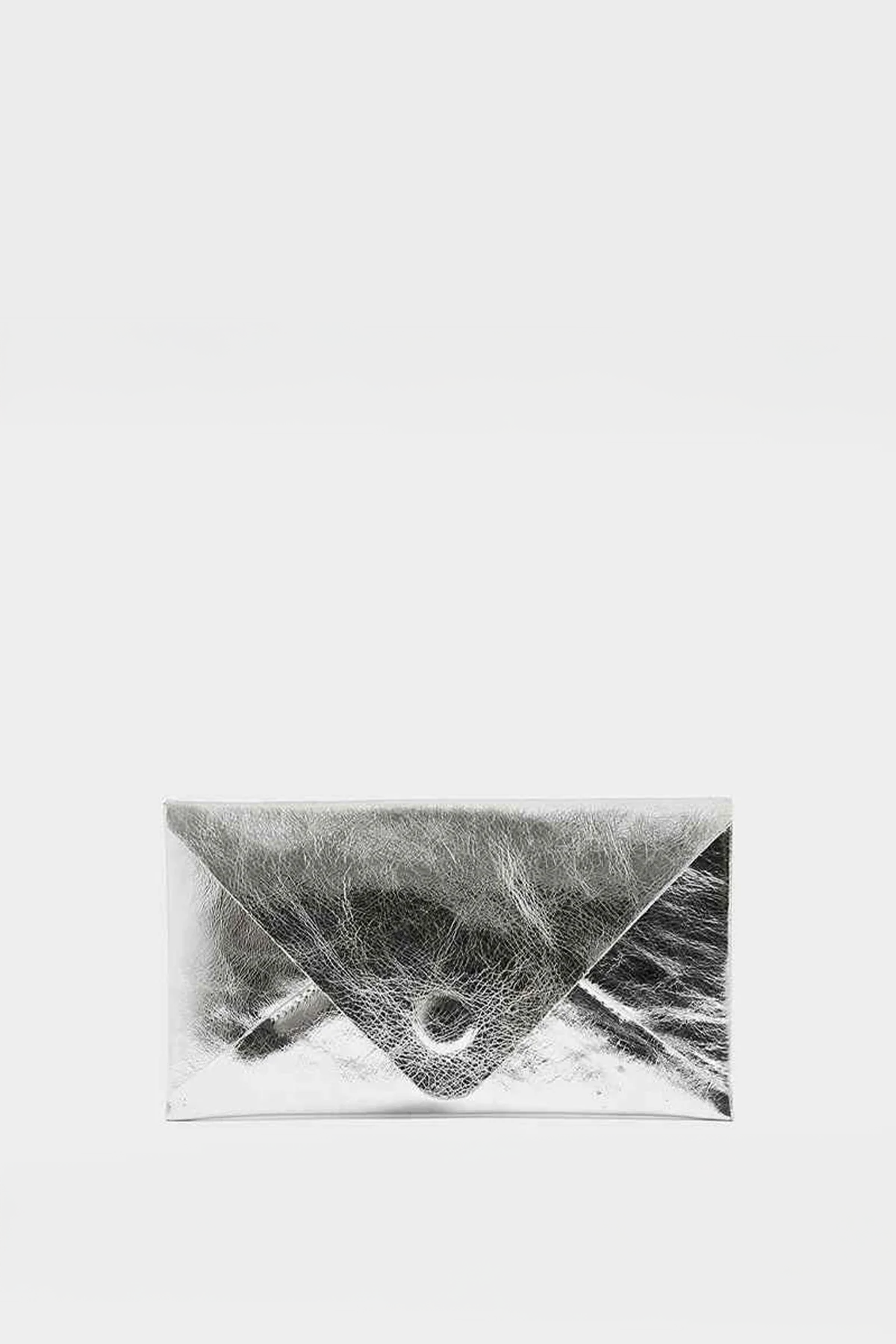

No, but really, what’s in your bag? Briskin-Rettig reaches deep into her latest prototype, a fourth-generation rebuild of her best-selling Bar bag on which she is “road-testing” a series of detachable shoulder straps for just the right hang. “It has been made, unpicked and remade,” she says, extricating a laptop, shoes — “I live in Suicoke sandals at work” — optical glasses, sunglasses, wallet, phone, phone charger, car keys and Maison Francis Kurkdjian fragrance from its infinite depths. “For me, the design process moves between the tangible and the intangible; but it starts with something that already exists, then deconstructs and reconstructs. It’s an evolution of the ideal; a body of observation digesting into a design. I’m always making the dream, not chasing it."

While the physical process plays out with her master pattern maker in a nearby Richmond atelier, where the slow-making with small-batch Italian leathers goes full-circle from concept to cut, to handcraft and final commercialisation in one space over one season, the evolution at home has eked out over 15 years. “And counting,” adds Briskin-Rettig, crediting her developer husband Andrew Rettig with “the vision” and vigour to transform a faded single-level brick house designed by modernist architect Tom Freeman (of Yuncken Freeman fame) into a genre-elusive wonderland that reminds of Los Angeles’s infamous Chateau Marmont after case-study architect Craig Ellwood fiddled with the bungalows in the 1950s.

There’s also a hint of quietly sumptuous Milanese rationalism in the meet of bordeaux marbles, patinated metals and herringbone timber floors à la the holistic glamour of Villa Necchi — “a favourite building discovered before [Luca Guadagnino’s film] I Am Love made it famous”. The house has seemingly grown by organic attrition, absorbing original walls, shutters and archways; growing out, over and under in every direction until past and present are indiscernible. “The things that make me stop now are scale, proportion and integration,” she says of what reins in a potential discordancy of Crittall heritage casement windows — “typically specked in UK libraries”; ’70s round-cornered coffered ceilings and standard ’60s lamps suggestive of the space age. “I keep referring back to experience and the things that subconsciously coalesce into one creative decision that then develops into another.”

“Iterative evolution” is the everywhere design force that allows for conversation to contain in a business-like block of brown Minotti croc-print chairs — “from Andrew’s bach-pad days” — or fall across a furry field of Edra seating in front of an original fireplace furnished with ’60s-style beanbags in granny-goes-berserk Italian florals. Of course, the ‘bagmeister’ Briskin-Rettig designed their pear-shaped laxity to offset the imperious posturing of Korean sculptures that have made the mantel their sovereign state.

They were the art punch in the solar plexus that incurred at Saatchi Gallery’s London showing of Korean Eye 2020 — a capture of the country’s best emerging and established contemporary artists. As much as the Rettigs remonstrate against being ‘informed’ collectors, the entry-flanking art corridor betrays a sharp grasp of the anachronisms, dreams and post-internet themes driving current markets.

“Andrew has an amazing eye,” says Briskin-Rettig suggesting that a walk through the winding rear garden — a veritable art park with seating pockets idealised and implemented by Rettig — will validate his 20-20 aesthetic vision. Clearly the couple are guided by their own deeply personal resonances and requirements for living well rather than any au courant dictates on design. “We just like rolling up our sleeves and getting hands on,” says Briskin-Rettig, refusing to blow the trumpet on innate talents. “This is totally us.”

When asked about her favourite pieces Briskin-Rettig picks up a stitched calico abstraction of a pigeon purchased at Rossana Orlandi’s Milan gallery, then pats an Art Deco porcelain bear rescued from a sea of mid-century modern pieces at Clignancourt Market in France. She rationalises their buy with the gut urge rather than any good resting place at home. Didn’t the big daddy of evolution Darwin declare that instinct follows independently of reason the question asks of Briskin-Rettig, who in all things design serially manifests his theory on ‘common descent with modification’; species changing slowly over time and giving rise to new ones.

Science is mystifying and marvellous, says Briskin-Rettig, but she leaves all natural selection to an A-esque clientele who buy into bags that survive and thrive in the fast-changing luxury landscape. ‘A’, it seems, is also for adaptability.

Written by Annemarie Kiely, Photography by Sean Fennessy