Good Weekend Style Edit May 2023

THE FIRST thing that hits you as you walk into A-esque’s Richmond headquarters is the aroma of leather. Good leather. Soft Italian leather. The kind my grandmother used to hold up to my nose as a child and say, in her thick central European accent: “Smell it. They don’t make it like this any more.” I inhale deeply as A-esque founder Amanda Rettig, dressed head-to-toe in black, flops on one of two sofas – black leather, of course – in the middle of this openplan warehouse. We’re in an inner-Melbourne suburb that’s home to designer furniture stores, cocktail bars and the MCG – but these days, thanks to high property prices, very few fashion businesses.

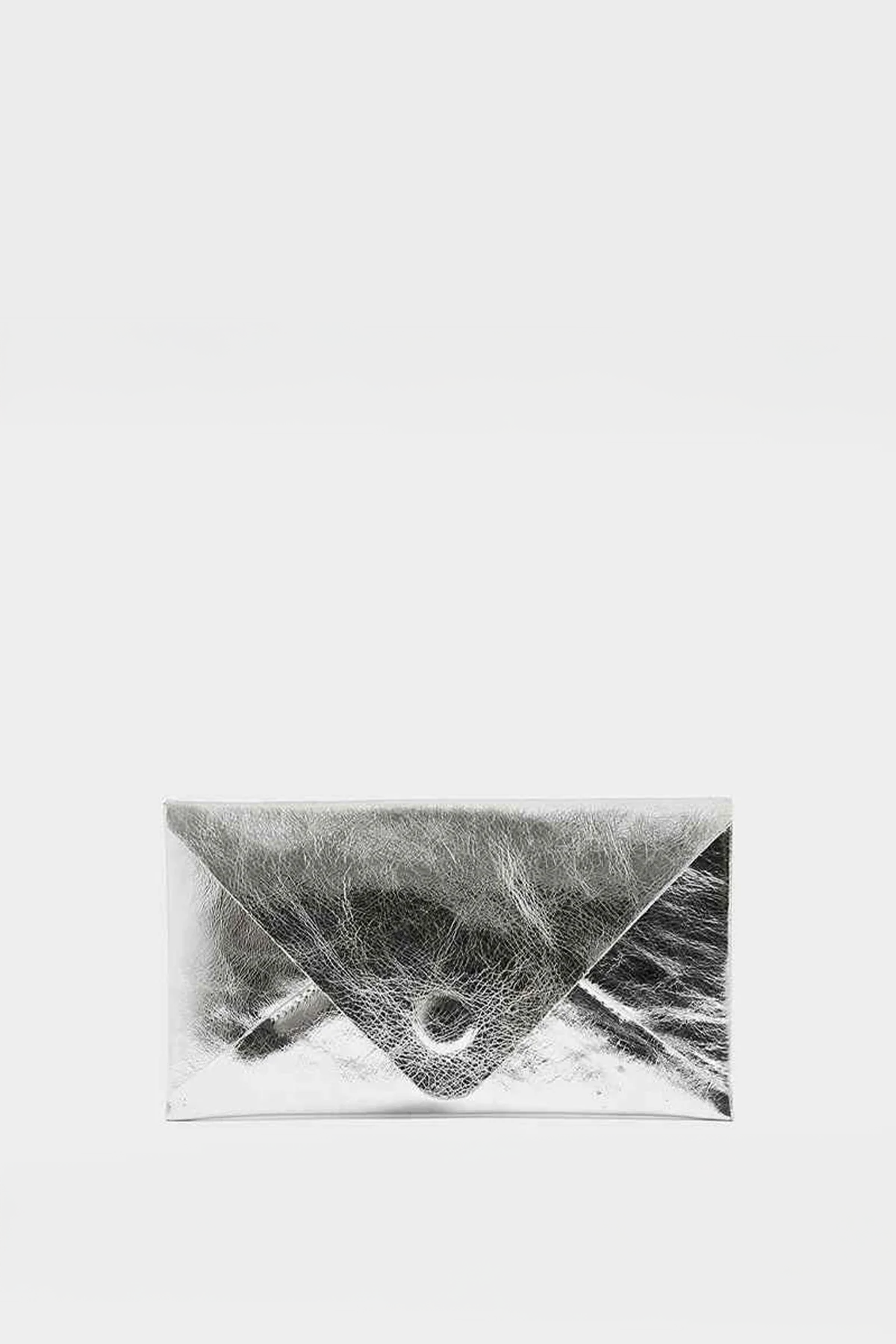

The space is divided into zones. At the front, hooks and shelves display bags of different shapes and sizes, from pillowy clutches that fit snugly under an arm to boxy carry-alls that hold everything from a laptop to a sippy-cup. Up the back, metal racks heave with rolls of leather. There’s a bookcase filled with ring binders – one for each style in the A-esque catalogue. And, taking up nearly half the room is the workspace, where a customer can see their bag being made – in real time, if they wish – before taking it home.

This hybrid model of manufacturing and retail feels both old and new. It has always been part of Rettig’s vision for A-esque, which turned 10 last year, but it took her most of the decade to bring it to fruition. The bags used to be made elsewhere in Richmond before being sent to wholesalers, online customers and the label’s three retail stores in Melbourne and Sydney.

But during the COVID-19 lockdowns, Rettig decided to close her shops and move everything, retail and manufacturing, into this one, consolidated space. Her aim is to host “meet the maker” nights and fashion parades here, for both her own and other independent Australian brands. The move reflects global attempts by many labels to bring their customers closer, extending the relationship beyond impersonal transactions that, these days, can be done from the comfort of a customer’s couch.

Before our meeting on an unusually warm, windy day in April, Rettig texts to say the atelier is quieter than usual due to the impending Easter break. But as I arrive, it’s humming: a sewing machine whirs, couriers deliver trolley-loads of leather and Rettig chats to a customer, a woman aged about 30, who is purchasing a small bag. If this is quiet, what does busy look like?

Rettig, 52, has spent most of her life in the fashion industry, having founded the Mimco accessories brand in 1996, when she went by her former name, Amanda Briskin. After selling her controlling stake to private equity in 2007 for a reported $30 million, Rettig spent a few years consulting to other labels. If she was going to do another bag brand, she decided, she wanted it to be smaller and “quieter” than Mimco, with an emphasis on quality and craftsmanship.

By the time she launched A-esque in 2012, “logomania” was massive, with luxury brands plastering their names on everything from bags to sweatshirts. In this sense, her range, which bears no obvious logos or insignia, was something of an outlier. “When A-esque started, it was very against the grain in terms of how strong branding was [as a trend],” Rettig says. “I was pretty confident that it would work. It didn’t make sense to me that human beings at large could only want brands that are owned by big fashion houses to define their style and accessories.” Rettig’s hunch was right. Over the past decade, bags by small independent brands, bearing little or no branding and often priced in the $500 to $1000 range – the so-called “affordable luxury” category – have become something of a sleeper hit. They still account for only a tiny slice of the Australian handbag market, which IBISWorld estimates to be worth $480 million annually. That market is dominated by Strandbags, Louis Vuitton and Mimco. Together with Luxottica, owner of Sunglass Hut, that trio accounts for nearly half of all accessories sold in Australia. But the indie maker is an emerging niche, particularly among discerning women interested in more than the latest fad.

Many younger women, in particular, have gravitated towards brands that eschew logos and other hallmarks of the traditional “It” bag, attracted in part by the tendency of smaller independent brands to focus on sustainable manufacturing. Even in China, where the market for designer bags is among the strongest globally, the number of locally produced, “indie” bag brands is growing.

Another thing that ties some of these brands together is a welcome return to practicality. These are bags for people who have things to carry and places to go, a contrast to the tiny-bag trend that peaked ahead of the pandemic, when some of the world’s most coveted styles couldn’t even fit an iPhone. As further proof of this snap back to utility, in April, global trend forecaster Lyst announced the most trending style of the past quarter: a $20 beige nylon satchel from multinational retailer Uniqlo.

PRACTICALITY, ALBEIT with a luxurious leaning, drove Wellington-based Jessie Wong to launch her bag business, Yu Mei, in 2015. When Wong, 29, was studying fashion design at Otago Polytechnic in Dunedin, she couldn’t find a bag she liked within her budget that fitted her laptop and lunchbox. So she started making them for herself, then for her friends, in the corner of a friend’s shop.

In a nod to both sustainability and tactility, most of Yu Mei’s bags are made from deer leather, a byproduct of New Zealand’s venison industry, which Wong sends to a factory in China. Wong says deer leather provides the strength of cowhide and the softness of lambskin, while also being lightweight, making it the ideal material for her larger styles, which retail for about $1500. What Wong finds interesting about her customers, who include former New Zealand prime minister Jacinda Ardern, is that most of them could easily afford pricier bags, but they choose to carry something less flashy that resonates with their values.

Like Rettig, Wong is trying to foster a community through a free membership program that offers access to events at her Auckland and Wellington stores. “We’ve created styles that really fit into our customers’ lives,” she says. “The majority of them could afford any bag, but it’s about saying, ‘I’m socially aware.’”

Another New Zealand brand with a strong social conscience is Deadly Ponies, which graphic designer Liam Bowden founded in 2005 as a way to teach himself new skills. He began making jewellery and bags in his Auckland garage; the closure of a nearby tannery eventually forced Bowden and his business partner and now-husband Steve Boyd to open their own factory in 2020 in northern Thailand.

Deadly Ponies details on its website where it sources each of its materials, from calf leather to mohair. Today’s customers want this kind of information, Bowden notes; labels can’t afford to treat transparency as an afterthought. Among the company’s other initiatives, customers get a $50 store credit for returning their Deadly Ponies bags that are beyond repair, which are then refurbished or stripped down and recycled into other goods, such as beanbags, key fobs or earbud holders. “They [Gen Z] want something that’s quality, there’s the sustainability factor – knowing where something is made, that it has some inherent value to the product,” Bowden says.

DEADLY PONIES recently expanded into shoes, beginning with 15 styles of boots, mules and slides that are made in Portugal and cost between $450 to $800. But not every brand wants to diversify. After expanding Mimco into jewellery, sunglasses and shoes, Rettig is keen for A-esque to remain a bag specialist.

Similarly, Bonnie Davis is in the process of paring back her brand, Dylan Kain, which she started 11 years ago with the goal of making functional, elegant bags that “look expensive” but only cost a few hundred dollars. Manufacturing in Australia proved prohibitively expensive. After pursuing a few options, she settled on China, where workers trained in Italy make the bags, which are then sold online and at department stores. Their branding is tiny, but the bags are identifiable by their silver hardware in the form of the Roman numerals I and II, a reference to Davis and her two sisters, one of whom is champion surfer Stephanie Gilmore. The range started small but over time, it ballooned into an array of colours and shapes that didn’t fit the brand’s ethos, says Davis. She’s in the process of editing the range back to six core styles. “For the next five or 10 years, I want to go back to what we’re known for ... because otherwise, you just end up homogenised with your competitors,” she says.

Returning to what sets these brands apart from their multinational competitors is a smart move in economically straitened times, which might, in the end, suit the boutique player with sensible pricing. Bridget Veals, general manager of womenswear and accessories at David Jones, has been charting the rise of the $500 to $1000 handbag for several years. She says Australian and New Zealand brands are performing well despite stiff international competition. “In this [economic] climate, we’ve seen more focus on buying [cheaper] leather goods, such as chain wallets. Customers are buying into more affordable price points with luxury designers,” she says, adding that sales of tote bags spiked as people returned to working in offices post-lockdowns.

Deadly Ponies’ Liam Bowden has noticed customers becoming more discerning, too, and taking more time to commit to a purchase. “Maybe it’s not as impulsive,” he says. For those championing quality, longevity and so-called “slow fashion”, that can only be a good thing.

Written by Melissa Singer, Photography by Peter Tarasiuk